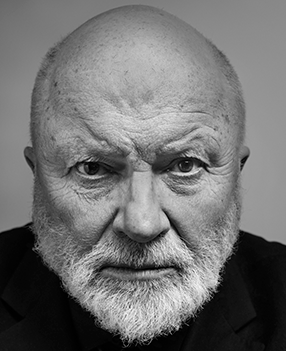

i.m. D S C H

I

Music’s poltergeist among the grand spirits,

can you now tell what such possession is

or was

saying: I know the woman who stands here

in Pushkin’s clock-haunted house,

shadowy figure nimbus’d by light’s mode

amid the wan company thinning at dawn.

The air sways, a lamp holds vigil

with its smoky flame.

The fiddle is in velvet, the cello

has ceased to urge her proud commodious song.

II

The cello’s long since ceased to urge her proud

commodious song. It is like a love story

that ends up tragic; or some common débâcle

heroic by decree.

There’s breach of custom that privileges laughter.

In art we hazard so much void of compulsion.

The silence and down-turned thumb are not

compulsion but luck, or the climate, being in the wrong place.

The sublime wearies, so we have farting on brass

like one of Stalin’s jokes. This is a sketched-in

historical thesis. You will call it parody.

III

You will call this parody yet your own music

is like a spectral dance more than a dance of spirits

when it is not

like a wide city under a bronze sky,

when it is not the Neva or a high voicing

of a passion-nocturne by Aleksandr Blok;

the unheard-of threnos brought into hearing

and, once heard, a presentiment from nature

no more to be wondered at

but in the broad way of wonder and acceptance.

Not parody precisely. It is true I think

IV

that I have now confused you with Zhivago

and Pushkin and my own ambition

to write Onegin and fifteen string quartets

and some sparely glittering poem about Christmas

or Easter;

to get the drum-raps right for cracking the spring ice:

more fitful as a human testament

than heart-murmur or tinnitus, or the way one’s jaw

creaks when eating. Finally I declare homage

to the late Frank O’Hara, intelligent, choosy

lover of Russia and of Russian music.

V

Who is this woman who stands here in Pushkin’s

clock-haunted house? I do not know.

I cannot

tell presence from memory amid the wan

company thinning at dawn. She is a muse

of sorts, that much is certain. Her hand

is nimbus’d in a gesture of rebuke

or blessing, and the lamp holds vigil

with its well-trimmed flame.

The house-door stands ajar. The cello has now long

languished from her immemorable aubade.

Copyright © 2024 by Geoffrey Hill. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on January 13, 2024, by the Academy of American Poets.

“Geoffrey Hill wrote ‘Genius Loci’ in the summer of 2004. It was one of the first poems he wrote as part of a new book, the volume A Treatise of Civil Power, which appeared in an abbreviated form as a pamphlet in 2005, and which was later published, after major revisions, in 2007. Those revisions include scrapping the long title poem for parts, adding new poems, and, in the case of ‘Genius Loci,’ withholding one of the additional poems from publication. This is a remarkable change, because at one stage ‘Genius Loci’ was to have been placed as the first poem of the whole volume. The poem is addressed to, and in memory of, Dmitri Shostakovich; the locus is Petersburg. It strikes a characteristic note of the whole book: the music is tragic and parodic, it is involved in but also withdraws from the history and politics of its time and its subsequent mythologizing.”

—Professor Kenneth Haynes