All Hallows Eve, Sweet Briar College, 2003

I came as a ghost to the party,

no costume required, I only had to wear

the brilliant skin, the ruinous eyes,

the body poised in transit, unwriting

the myth of sex. I came as a ghost

to the party, though we pretended

not to notice a palpable hovering

in the interstices of conversations,

a presence so insubstantial

eyes passed through it, hands

reached through air, bodies jostled

on the dance floor and never felt a thing.

Still, some there were haunted,

drawn away from the company,

its clenched knots of desperate clever banter,

to contemplate the thinnest air

as if, despite themselves,

they heard and heeded a ghostly tongue;

their bodies swayed in answer.

Staring into that void they glimpsed themselves,

turned back, shuddering, to the masquerade.

I came as a ghost to the party

against my better judgment

at the persistent, earnest

urging of my friends, as if

a ghost had friends when they hoist

the flag of whiteness and huddle there

under purity and privilege, surrender—fatal—

the furious, frailer, darker parts

of themselves. Recently they had rallied

to kiss the ass of a black man who had accomplished

admirable things—though most there had not read

them or only read a story,

as pleasantly exotic and sweetly soothing

as those wonderful spirituals

about wading in the water and summertime.

So extravagant was their ardor

that I, a member of his tribe,

could not get near him or have one word.

Still, I know he saw me, sitting there, tense, alone,

before his lecture, unmoored and vanishing

in the cocktail Hell before his dinner—

did not only see, but recognized a kindred ache.

The first and second and third rule of thumb,

the commentator said, is do not scare

the white people. And so we stand apart,

raise no specters of over-educated house

niggers breeding insurrections, mustering

ghost armies of strangers, lepers, freaks,

the wretched of the earth, furious,

innumerable and not afraid to die.

I came as a ghost to the party.

you didn’t wear a costume, someone said.

I came as an activist, I replied,

modeling my black ACLU t-shirt,

Lady Liberty emblazoned down my front,

at my back, a litany of rights.

I might have said the costume’s in the eye.

You will weave for me a shroud

and I will walk among you like a ghost,

mask of the red death, memento mori.

Blind with pride and rage

(I will ask no one for help), I quit the place,

leave the lake behind, the band’s god-awful

din, the strafing voices—the rent

in the world’s fabric miraculously healed

by my going. The dark deserted road

is unfamiliar, its grade, its curves,

the woods casting shadows from either side,

but any path is right that leads away.

I lose my way, keep going, going,

deeper into the maze, finally turn back.

Returned, the band’s on break;

They’ve put a mix tape in.

I dance like one possessed, furious grace.

When strangers, not of this place,

say a quick goodnight, I run after,

take me with you, I say.

A solid hand upon my solid knee, warm hands

returning the pressure of my warm hand—

two women rescue me, deliver me—

ghost in the machine

once more human girl—home

with promises of brunch and company

they will or will not keep.

No matter. I lock the door

and slide the chain, rest back against

the frame, breathing relief.

May they all die horribly in a boathouse fire.

The malediction takes me by surprise.

I say it once again with clear intent:

May they all die horribly in a boathouse fire.

These words be kerosene, dry wood, locked doors, a match.

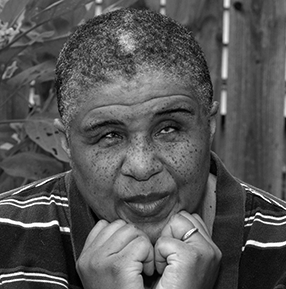

From Blind Girl Grunt: The Selected Blues Lyrics and Other Poems (Headmistress Press, 2017). Copyright © 2017 by Constance Merritt. Used with the permission of the author.