Kind of empty in the way it sees everything, the earth gets to its feet and

salutes the sky. More of a success at it this time than most

others it is. The feeling that the sky might be in the back of someone's

mind. Then there is no telling how many there are. They grace

everything--bush and tree--to take the roisterer's mind off his

caroling--so it's like a smooth switch back. To what was aired in

their previous conniption fit. There is so much to be seen everywhere

that it's like not getting used to it, only there is so much it

never feels new, never any different. You are standing looking at that

building and you cannot take it all in, certain details are already hazy

and the mind boggles. What will it all be like in five years' time

when you try to remember? Will there have been boards in between the

grass part and the edge of the street? As long as that couple is

stopping to look in that window over there we cannot go. We feel like

they have to tell us we can, but they never look our way and they are

already gone, gone far into the future--the night of time. If we could

look at a photograph of it and say there they are, they never really

stopped but there they are. There is so much to be said, and on the

surface of it very little gets said.

There ought to be room for more things, for a spreading out, like.

Being immersed in the details of rock and field and slope --letting them

come to you for once, and then meeting them halfway would be so much

easier--if they took an ingenuous pride in being in one's blood.

Alas, we perceive them if at all as those things that were meant to be

put aside-- costumes of the supporting actors or voice trilling at the

end of a narrow enclosed street. You can do nothing with them. Not even

offer to pay.

It is possible that finally, like coming to the end of a long,

barely perceptible rise, there is mutual cohesion and interaction. The

whole scene is fixed in your mind, the music all present, as though you

could see each note as well as hear it. I say this because there is an

uneasiness in things just now. Waiting for something to be over before

you are forced to notice it. The pollarded trees scarcely bucking the

wind--and yet it's keen, it makes you fall over. Clabbered sky.

Seasons that pass with a rush. After all it's their time

too--nothing says they aren't to make something of it. As for Jenny

Wren, she cares, hopping about on her little twig like she was tryin'

to tell us somethin', but that's just it, she couldn't

even if she wanted to--dumb bird. But the others--and they in some way

must know too--it would never occur to them to want to, even if they

could take the first step of the terrible journey toward feeling

somebody should act, that ends in utter confusion and hopelessness, east

of the sun and west of the moon. So their comment is: "No comment."

Meanwhile the whole history of probabilities is coming to life, starting

in the upper left-hand corner, like a sail.

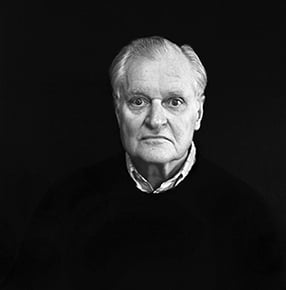

Credit

From The Mooring of Starting Out: The First Five Books of Poetry, by John Ashbery, published by The Ecco Press. Copyright © 1956 by John Ashbery. Used with permission.

Date Published

01/01/1956