Luxurious man, to bring his vice in use,

Did after him the world seduce,

And from the fields the flowers and plants allure,

Where nature was most plain and pure.

He first enclosed within the garden's square

A dead and standing pool of air,

And a more luscious earth for them did knead,

Which stupefied them while it fed.

The pink grew then as double as his mind:

The nutriment did change the kind.

With strange perfumes he did the roses taint,

And flowers themselves were taught to paint.

The tulip, white, did for complexion seek,

And learned to interline its cheek;

Its onion root they then so high did hold,

That one was for a meadow sold.

Another world was searched, through oceans new,

To find the marvel of Peru.

And yet these rarities might be allowed,

To man, that sovereign thing, and proud,

Had he not dealt between the bark and tree,

Forbidden mixtures there to see.

No plant now knew the stock from which it came;

He grafts upon the wild the tame,

That the uncertain and adulterate fruit

Might put the palate in dispute.

His green seraglio has its eunuchs too,

Lest any tyrant him outdo,

And in the cherry he does nature vex,

To procreate without a sex.

'Tis all enforced—the fountain and the grot—

While the sweet fields do lie forgot,

Where willing nature does to all dispense

A wild and fragrant innocence,

And fauns and fairies do the meadows till

More by their presence than their skill.

Their statues, polished by some ancient hand,

May to adorn the gardens stand,

But how so'er the figures do excel,

The gods themselves with us do dwell.

This poem appeared in Poem-A-Day on March 31, 2013. Browse the Poem-A-Day archive. This poem is in the public domain.

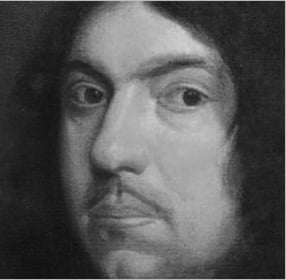

In his essay, "Andrew Marvell," T. S. Eliot writes that "Wit is not a quality that we are accustomed to associate with "Puritan" literature, with Milton or with Marvell. But if so, we are at fault partly in our conception of wit and partly in our generalizations about the Puritans.