It's as if every demon from hell with aspirations toward interior design flew overhead and indiscriminately spouted gouts of molten gold, that cooled down into swan-shape spigots, doorknobs, pen-and-inkwell sets. A chandelier the size of a planetarium dome is gold, and the commodes. The handrails heading to the wine cellar and the shelving for the DVDs and the base for the five stuffed tigers posed in a fighting phalanx: gold, as is the samovar and the overripe harp and the framework for the crocodile-hide ottoman and settee. The full-size cinema theater accommodating an audience of hundreds for the screening of home (or possibly high-end fuck flick) videos: starred in gold from vaulted ceiling to clawfoot legs on the seating. Of course the scepter is gold, but the horns on the mounted stag heads: do they need to be gilded? Yes. And the olive fork and the French maid's row of dainty buttons and the smokestack on the miniature train that delivers golden trays of dessert from the kitchen to a dining hall about the size of a zip code, and the snooker table's sheathing, and the hat rack, and those hooziewhatsit things in which you slip your feet on the water skis, and the secret lever that opens the door to the secret emergency bunker. Smug and snarky as we are, in our sophisticated and subtler, non-tyrannical tastes, it's still unsettling to realize these photographs are also full of the childrens' pictures set on a desk, the wife's diploma proudly on a wall, the common plastic container of aspirin, and the bassinette with the scroll of linen shade at the ready in case the sun is too powerful: reminders of how a graduated continuum connects these überoperatically fat interior lives to our own. We all desire "more" and "better," Melville adds that final "e" to the family name, and Faulkner adds the "u," in quest of a signified gentility. My friend Damien (fake name) won A Certain Literary Award, and at the stellar after-ceremony party, in the swank hotel's swank atrium, he found a leggy literary groupie noshing caviar under a swankily lush mimosa, and in under an hour his own swank room could boast the golden statuette, the evening's loveliest woman, and the silver serving platter of five-star caviar, and if you think this story's moral lesson is that satiation is ever attained, you don't understand the protoknowledge we're born with, coded into our cells: soon soon soon enough we die. Even before we've seen the breast, we're crying to the world that we want; and the world doles out its milkiness in doses. We want, we want, we want, and if we don't then that's what we want; abstemiousness is only hunger translated into another language. Yes there's pain and heartsore rue and suffering, but there's no such thing as "anti-pleasure": it's pleasure that the anchorite takes in his bleak cave and Thoreau in his bean rows and cabin. For Thoreau, the Zen is: wanting less is wanting more. Of less. At 3 a.m. Marlene (fake name) and Damien drunkenly sauntered into and out of the atrium, then back to his room: he wanted the mimosa too, and there it stood until checkout at noon, a treenapped testimony to the notion that we will if we can, as evidenced in even my normally modest, self-effacing friend. If we can, the archeological record tells us, we'll continue wanting opulently even in the afterlife: the grave goods of pharaohs are just as gold as the headrests and quivers and necklace pendants they used every day on this side of the divide, the food containers of Chinese emperors are ready for heavenly meals that the carved obsidian dragons on the great jade lids will faithfully guard forever. My own innate definition of "gratification" is right there in its modifier "immediate," and once or twice I've hurt somebody in filling my maw. I've walked —the normally modest, self-effacing me—below a sky of stars I lusted after as surely as any despot contemplating his treasury. The slice of American cheese on the drive-thru-window burger is also gold, bathetically gold, and I go where my hunger dictates.

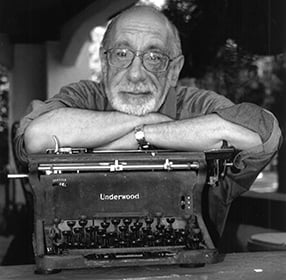

Credit

From Everyday People by Albert Goldbarth. Copyright © 2012 by Albert Goldbarth. Reprinted with permission of Graywolf Press. All rights reserved.

Date Published

01/01/2012