Dedicated to the memory of Paul Laurence Dunbar

Oh, Poet of our Race,

We reverence thy name

As thy hist’ry we retrace,

Which enfolds thy widespread fame.

We loved thee, yea, too well,

But He dids’t love thee more

And called thee up with Him to dwell

On that Celestial shore.

Thy sorrows here on earth,

Yea, more than thou coulds’t bear,

Burdened thee from birth

E’en in their visions fair.

And thou, adored of men,

Whose bed might been of flowers,

With mighty stroke of pen

Expressed thy sad, sad hours.

Thou hast been called above,

Where all is peace and rest,

To dwell in boundless love,

Eternally and blest.

And, yet, thou still dost linger near,

For thy words, as sweetest flowers,

Do grow in beauty ’round us here

To cheer us in saddest hours.

Thy thoughts in rapture seem to soar

So far, yea, far above,

And shower a heavy downpour

Of sparkling, glittering love.

Thou, with stroke of mighty pen,

Hast told of joy and mirth,

And read the hearts and souls of men

As cradled from their birth.

The language of the flowers,

Thou hast read them all,

And e’en the little brook

Responded to thy call.

All Nature hast communed

And lingered, yea, with thee,

Their secrets were entombed

But thou hast made them free.

Oh, Poet of our Race,

Thou dost soar above;

No paths wilt thou retrace

But those of peace and love.

Thy pilgrimage is done,

Thy toils on earth are o’er,

Thy victor’s crown is won,

Thou’lt rest forever more.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on February 11, 2024, by the Academy of American Poets.

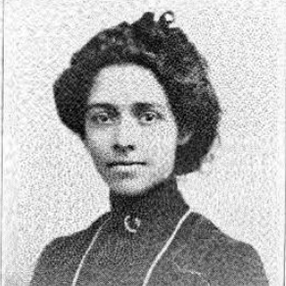

“Poet of Our Race” appeared in Pogue Johnson’s first known poetry collection, Virginia Dreams (John M. Leonard, 1910), and is an example of dialect poetry, where accents and speech patterns are reproduced within the poem. In Rhetorics of Literacy: The Cultivation of American Dialect Poetry (Ohio State University Press, 2013), Nadia Nurhussein writes, “[D]ialect writing at the turn of the [twentieth] century was written primarily by men, as the genre was considered culturally inappropriate for women. (The stylistically divergent careers of married poets Paul Laurence Dunbar and Alice Dunbar-Nelson illustrate this point.) In this cultural milieu, [...] Johnson chose to write and publish dialect poems” and her poems “dealt explicitly with the process of literacy acquisition,” while “linking dialect poetry with leisure.” Nurhessein also asserts in Virginia Dreams, “Maggie Pogue Johnson […] chooses to present her dialect poetry not in a cloak of blank asexuality but in a deliberate and emphatic masculine disguise; her speakers are often men. This move is not uncommon among African American women poets who wanted to take advantage of dialect poetry’s popularity and goals at the turn of the century without sacrificing the appearance of bourgeois gentility.”