The ringèd moon sits eerily

Like a mad woman in the sky,

Dropping flat hands to caress

The far world’s shaggy flanks and breast,

Plunging white hands in the glade

Elbow deep in leafy shade

Where birds sleep in each silent brake

Silverly, there to wake

The quivering loud nightingales

Whose cries like scattered silver sails

Spread across the azure sea.

Her hands also caress me:

My keen heart also does she dare;

While turning always through the skies

Her white feet mirrored in my eyes

Weave a snare about my brain

Unbreakable by surge or strain,

For the moon is mad, for she is old,

And many’s the bead of a life she’s told;

And many’s the fair one she’s seen wither:

They pass, they pass, and know not whither.

The hushèd earth, so calm, so old,

Dreams beneath its heath and wold—

And heavy scent from thorny hedge

Paused and snowy on the edge

Of some dark ravine, from where

Mists as soft and thick as hair

Float silver in the moon.

Stars sweep down—or are they stars?—

Against the pines’ dark etchèd bars.

Along a brooding moon-wet hill

Dogwood shine so cool and still,

Like hands that, palm up, rigid lie

In invocation to the sky

As they spread there, frozen white,

Upon the velvet of the night.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on April 30, 2023, by the Academy of American Poets.

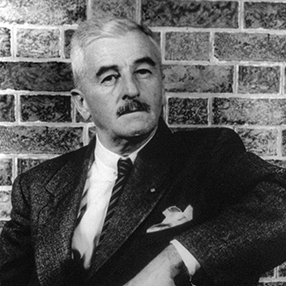

“[The ringèd moon sits eerily]” appears in William Faulkner’s first book, a sequence of poems titled The Marble Faun (The Four Seas Company, 1924). As literary critic Cleanth Brooks writes in William Faulkner: Toward Yoknapatawpha and Beyond (Louisiana State University Press, 1978), the young Faulkner “may have borrowed his metrical pattern (octosyllabic couplets) from William Butler Yeats’s ‘The Song of the Happy Shepherd’ [. . .].” In “Faulkner and the Southern Symbolism of Pastoral,” published in The Mississippi Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 4 (Fall 1975), Lewis P. Simpson, former Boyd Professor and William A. Read Professor of English at Louisiana State University, writes that “Faulkner’s first published book, The Marble Faun, is a carefully constructed exercise in pastoral, ironically implying the rejection of pastoral by modernity, and, I believe, more particularly in his own vision. ‘Sad for things I know, yet cannot know,’ his marbelized [sic] Faun muses in ‘an old garden’ through a progression of poems ordered according to the conventional English eclogue by the cycle of the seasons and the hours of the day. The things that the Faun knows but can’t know are those things which modern history has deprived him of the capacity to know. He stands fixed in a disposessed garden—isolated in his own consciousness [. . .]. In The Marble Faun the pastoral mode becomes a symbol of the modern solipsistic state.”