The sandy spits, the shore-lock’d lakes,

Melt into open, moonlit sea;

The soft Mediterranean breaks

At my feet, free.

Dotting the fields of corn and vine

Like ghosts, the huge, gnarl’d olives stand;

Behind, that lovely mountain-line!

While by the strand

Cette, with its glistening houses white,

Curves with the curving beach away

To where the lighthouse beacons bright

Far in the bay.

Ah, such a night, so soft, so lone,

So moonlit, saw me once of yore

Wander unquiet, and my own

Vext heart deplore!

The murmur of this Midland deep

Is heard to-night around thy grave

There where Gibraltar’s cannon’d steep

O’erfrowns the wave.

In cities should we English lie,

Where cries are rising ever new,

And men’s incessant stream goes by;

We who pursue

Our business with unslackening stride,

Traverse in troops, with care-fill’d breast,

The soft Mediterranean side,

The Nile, the East,

And see all sights from pole to pole,

And glance, and nod, and bustle by;

And never once possess our soul

Before we die.

Not by those hoary Indian hills,

Not by this gracious Midland sea

Whose floor to-night sweet moonshine fills,

Should our graves be!

Some sage, to whom the world was dead,

And men were specks, and life a play;

Who made the roots of trees his bed,

And once a day

With staff and gourd his way did bend

To villages and homes of man,

For food to keep him till he end

His mortal span,

And the pure goal of Being reach;

Grey-headed, wrinkled, clad in white,

Without companion, without speech,

By day and night

Pondering God’s mysteries untold,

And tranquil as the glacier snows––

He by those Indian mountains old

Might well repose!

Some grey crusading knight austere

Who bore Saint Louis company

And came home hurt to death and here

Landed to die;

Some youthful troubadour whose tongue

Fill’d Europe once with his love-pain,

Who here outwearied sunk, and sung

His dying strain;

Some girl who here from castle-bower,

With furtive step and cheek of flame,

’Twixt myrtle-hedges all in flower

By moonlight came

To meet her pirate-lover’s ship,

And from the wave-kiss’d marble stair

Beckon’d him on, with quivering lip

And unbound hair,

And lived some moons in happy trance,

Then learnt his death, and pined away––

Such by these waters of romance

’Twas meet to lay!

But you––a grave for knight or sage,

Romantic, solitary, still,

O spent ones of a work-day age!

Befits you ill.

So sang I; but the midnight breeze

Down to the brimm’d moon-charmed main

Comes softly through the olive-trees,

And checks my strain.

I think of her, whose gentle tongue

All plaint in her own cause controll’d;

Of thee I think, my brother! young

In heart, high-soul’d;

That comely face, that cluster’d brow,

That cordial hand, that bearing free,

I see them still, I see them now,

Shall always see!

And what but gentleness untired,

And what but noble feeling warm,

Wherever shown, howe’er attired,

Is grace, is charm?

What else is all these waters are,

What else is steep’d in lucid sheen,

What else is bright, what else is fair,

What else serene?

Mild o’er her grave, ye mountains, shine!

Gently by his, ye waters, glide!

To that in you which is divine

They were allied.

This poem is in the public domain. Published in Poem-a-Day on March 9, 2024, by the Academy of American Poets.

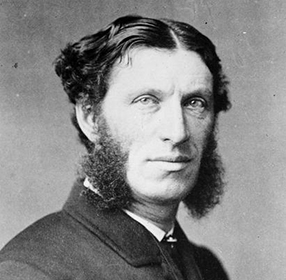

“A Southern Night” was first published in The Victoria Regia magazine in 1861 and reprinted in Matthew Arnold’s poetry collection, New Poems (Macmillan and Co., 1867). The poem also appears in The Poems Of Matthew Arnold, 1840–1867, which was published in 1913 by Oxford University Press. In the book’s introduction, literary critic and writer Arthur T. Quiller-Couch wrote, “A Southern Night may seem almost too exquisitely elaborated. Yet who can think of Arnold’s poetry as a whole without feeling that Nature is always behind it as a living background?—whether it be the storm of wind and rain shaking Tintagel […] or the scent-laden water-meadows along [the] Thames, or the pine forests on the flank of Etna, or an English garden in June, or [the] Oxus, its mists and fens and ‘the hush’d Choroasman waste.’ If Arnold’s love of natural beauty have not those moments of piercing apprehension which in his master’s poetry seem to break through dullness into the very heaven […].”