—The Carpathian Frontier, October, 1968

—for my brother

Once, in a foreign country, I was suddenly ill.

I was driving south toward a large city famous

For so little it had a replica, in concrete,

In two-thirds scale, of the Arc de Triomphe stuck

In the midst of traffic, & obstructing it.

But the city was hours away, beyond the hills

Shaped like the bodies of sleeping women.

Often I had to slow down for herds of goats

Or cattle milling on those narrow roads, & for

The narrower, lost, stone streets of villages

I passed through. The pains in my stomach had grown

Gradually sharper & more frequent as the day

Wore on, & now a fever had set up house.

In the villages there wasn't much point in asking

Anyone for help. In those places, where tanks

Were bivouacked in shade on their way back

From some routine exercise along

The Danube, even food was scarce that year.

And the languages shifted for no clear reason

From two hard quarries of Slavic into German,

Then to a shred of Latin spliced with oohs

And hisses. Even when I tried the simplest phrases,

The peasants passing over those uneven stones

Paused just long enough to look up once,

Uncomprehendingly. Then they turned

Quickly away, vanishing quietly into that

Moment, like bark chips whirled downriver.

It was autumn. Beyond each village the wind

Threw gusts of yellowing leaves across the road.

The goats I passed were thin, gray; their hind legs,

Caked with dried shit, seesawed along—

Not even mild contempt in their expressionless,

Pale eyes, & their brays like the scraping of metal.

Except for one village that had a kind

Of museum where I stopped to rest, & saw

A dead Scythian soldier under glass,

Turning to dust while holding a small sword

At attention forever, there wasn't much to look at.

Wind, leaves, goats, the higher passes

Locked in stone, the peasants with their fate

Embroidering a stillness into them,

And a spell over all things in that landscape,

Like . . .

That was the trouble; it couldn't be

Compared to anything else, not even the sleep

Of some asylum at a wood's edge with the sound

Of a pond's spillway beside it. But as each cramp

Grew worse & lasted longer than the one before,

It was hard to keep myself aloof from the threadbare

World walking on that road. After all,

Even as they moved, the peasants, the herds of goats

And cattle, the spiralling leaves, at least were part

Of that spell, that stillness.

After a while,

The villages grew even poorer, then thinned out,

Then vanished entirely. An hour later,

There were no longer even the goats, only wind,

Then more & more leaves blown over the road, sometimes

Covering it completely for a second.

And yet, except for a random oak or some brush

Writhing out of the ravine I drove beside,

The trees had thinned into rock, into large,

Tough blonde rosettes of fading pasture grass.

Then that gave out in a bare plateau. . . . And then,

Easing the Dacia down a winding grade

In second gear, rounding a long, funneled curve—

In a complete stillness of yellow leaves filling

A wide field—like something thoughtlessly,

Mistakenly erased, the road simply ended.

I stopped the car. There was no wind now.

I expected that, & though I was sick & lost,

I wasn't afraid. I should have been afraid.

To this day I don't know why I wasn't.

I could hear time cease, the field quietly widen.

I could feel the spreading stillness of the place

Moving like something I'd witnessed as a child,

Like the ancient, armored leisure of some reptile

Gliding, gray-yellow, into the slightly tepid,

Unidentical gray-brown stillness of the water—

Something blank & unresponsive in its tough,

Pimpled skin—seen only a moment, then unseen

As it submerged to rest on mud, or glided just

Beneath the lustreless, calm yellow leaves

That clustered along a log, or floated there

In broken ringlets, held by a gray froth

On the opaque, unbroken surface of the pond,

Which reflected nothing, no one.

And then I remembered.

When I was a child, our neighbors would disappear.

And there wasn't a pond of crocodiles at all.

And they hadn't moved. They couldn't move. They

Lived in the small, fenced-off backwater

Of a canal. I'd never seen them alive. They

Were in still photographs taken on the Ivory Coast.

I saw them only once in a studio when

I was a child in a city I once loved.

I was afraid until our neighbor, a photographer,

Explained it all to me, explained how far

Away they were, how harmless; how they were praised

In rituals as "powers." But they had no "powers,"

He said. The next week he vanished. I thought

Someone had cast a spell & that the crocodiles

Swam out of the pictures on the wall & grew

Silently & multiplied & then turned into

Shadows resting on the banks of lakes & streams

Or took the shapes of fallen logs in campgrounds

In the mountains. They ate our neighbor, Mr. Hirata.

They ate his whole family. That is what I believed,

Then. . .that someone had cast a spell. I did not

Know childhood was a spell, or that then there

Had been another spell, too quiet to hear,

Entering my city, entering the dust we ate. . . .

No one knew it then. No one could see it,

Though it spread through lawnless miles of housing tracts,

And the new, bare, treeless streets; it slipped

Into the vacant rows of warehouses & picked

The padlocked doors of working-class bars

And union halls & shuttered, empty diners.

And how it clung! (forever, if one had noticed)

To the brothel with the pastel tassels on the shade

Of an unlit table lamp. Farther in, it feasted

On the decaying light of failing shopping centers;

It spilled into the older, tree-lined neighborhoods,

Into warm houses, sealing itself into books

Of bedtime stories read each night by fathers—

The books lying open to the flat, neglected

Light of dawn; & it settled like dust on windowsills

Downtown, filling the smug cafés, schools,

Banks, offices, taverns, gymnasiums, hotels,

Newsstands, courtrooms, opium parlors, Basque

Restaurants, Armenian steam baths,

French bakeries, & two of the florists' shops—

Their plate glass windows smashed forever.

Finally it tried to infiltrate the exact

Center of my city, a small square bordered

With palm trees, olives, cypresses, a square

Where no one gathered, not even thieves or lovers.

It was a place which no longer had any purpose,

But held itself aloof, I thought, the way

A deaf aunt might, from opinions, styles, gossip.

I liked it there. It was completely lifeless,

Sad & clear in what seemed always a perfect,

Windless noon. I saw it first as a child,

Looking down at it from that as yet

Unvandalized, makeshift studio.

I remember leaning my right cheek against

A striped beach ball so that Mr. Hirata—

Who was Japanese, who would be sent the next week

To a place called Manzanar, a detention camp

Hidden in stunted pines almost above

The Sierra timberline—could take my picture.

I remember the way he lovingly relished

Each camera angle, the unwobbling tripod,

The way he checked each aperture against

The light meter, in love with all things

That were not accidental, & I remember

The care he took when focusing; how

He tried two different lens filters before

He found the one appropriate for that

Sensual, late, slow blush of afternoon

Falling through the one broad bay window.

I remember holding still & looking down

Into the square because he asked me to;

Because my mother & father had asked me please

To obey & be patient & allow the man—

Whose business was failing anyway by then—

To work as long as he wished to without any

Irritations or annoyances before

He would have to spend these years, my father said,

Far away, in snow, & without his cameras.

But Mr. Hirata did not work. He played.

His toys gleamed there. That much was clear to me . . . .

That was the day I decided I would never work.

It felt like a conversion. Play was sacred.

My father waited behind us on a sofa made

From car seats. One spring kept nosing through.

I remember the camera opening into the light . . . .

And I remember the dark after, the studio closed,

The cameras stolen, slivers of glass from the smashed

Bay window littering the unsanded floors,

And the square below it bathed in sunlight . . . . All this

Before Mr. Hirata died, months later,

From complications following pneumonia.

His death, a letter from a camp official said,

Was purely accidental. I didn't believe it.

Diseases were wise. Diseases, like the polio

My sister had endured, floating paralyzed

And strapped into her wheelchair all through

That war, seemed too precise. Like photographs . . .

Except disease left nothing. Disease was like

And equation that drank up light & never ended,

Not even in summer. Before my fever broke,

And the pains lessened, I could actually see

Myself, in the exact center of that square.

How still it had become in my absence, & how

Immaculate, windless, sunlit. I could see

The outline of every leaf on the nearest tree,

See it more clearly than ever, more clearly than

I had seen anything before in my whole life:

Against the modest, dark gray, solemn trunk,

The leaves were becoming only what they had to be—

Calm, yellow, things in themselves & nothing

More—& frankly they were nothing in themselves,

Nothing except their little reassurance

Of persisting for a few more days, or returning

The year after, & the year after that, & every

Year following—estranged from us by now—& clear,

So clear not one in a thousand trembled; hushed

And always coming back—steadfast, orderly,

Taciturn, oblivious—until the end of Time.

Credit

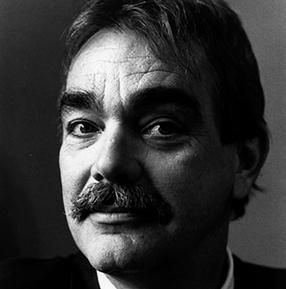

From The Widening Spell of the Leaves by Larry Levis, published by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Copyright © 1991 by the estate of Larry Levis. Reproduced by permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved.

Date Published

01/01/1991